EVs Aren’t Lowering CO2 Emissions Because SUVs Are Too Popular

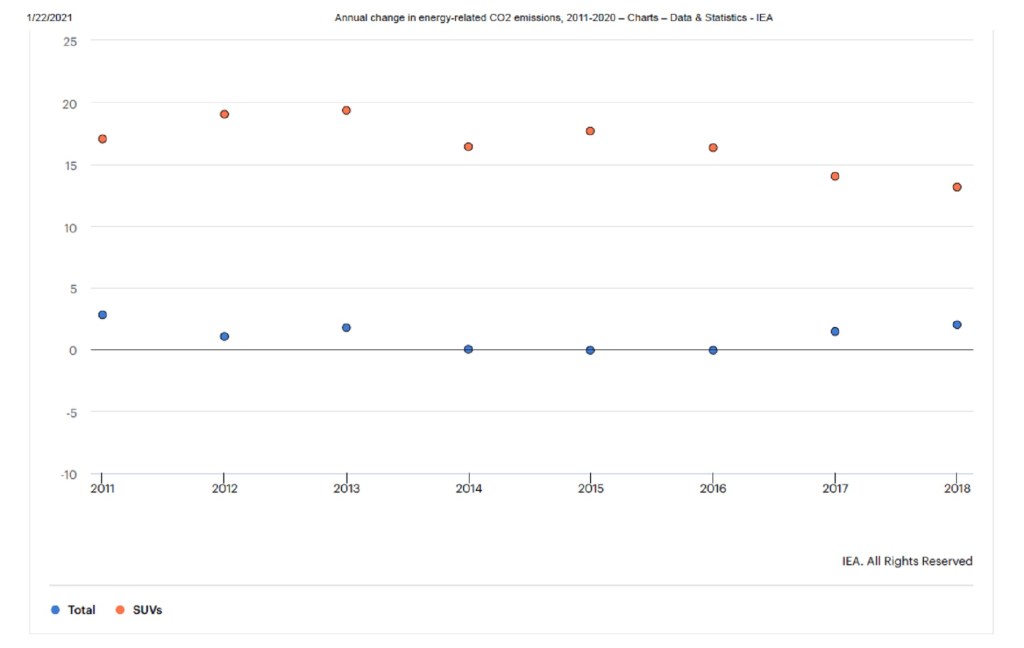

The rise and development of EVs haven’t exactly gone smoothly. But, while the electricity they use to recharge isn’t always 100% clean, electric cars do produce fewer emissions, CO2 and otherwise, than ICE ones. That’s why there’s been such a push to replace gasoline and diesel vehicles with battery-powered ones. However, a new report from the International Energy Agency shows that, despite growing sales, EVs haven’t curtailed CO2 emissions. And it’s because of SUVs.

High SUV sales cancel out the CO2 emissions savings from EVs, says a new IEA report

SUV and truck sales have been consistently rising over the past few years. So much so that in 2019, the number of off-lease SUVs and trucks surpassed that of off-lease passenger cars. And for those interested in curtailing automotive CO2 emissions, that’s a problem.

In a recent report, the IEA examined the change in CO2 emissions across multiple sectors over 2020. The agency looked at power generation, heavy industry, long-distance transportation, and personal vehicles.

Naturally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, vehicular traffic decreased—and thus, so did CO2 emissions. In fact, the Global Carbon Project found that worldwide CO2 emissions dropped 7% because of the pandemic, Autoblog reports. It’s the largest drop in modern history, The Drive reports. And it comes with a commensurate improvement in air quality, Autoblog reports.

Except SUVs weren’t affected. Uniquely across the analyzed sectors, SUV-related CO2 emissions actually increased during 2020. Even as oil use by non-SUV ICE vehicles dropped, SUVs used more oil in 2020 than they did in 2019. So much so, that the growth in EVs’ market presence was “completely cancelled out,” the IEA reports.

However, the agency reports that this wasn’t because SUV owners were driving more than EV or other ICE vehicle owners. It’s because SUV sales were so high that they canceled out the decrease in driving. Essentially, SUVs have become so popular that they’re making up for the CO2 emissions the EVs don’t produce.

It’s worth pointing out that what the IEA refers to as ‘SUVs’ also includes crossovers. Technically, crossovers aren’t SUVs, but in the eyes of the public and marketing, the two are often synonymous. So, technically, the popularity of crossovers and SUVs are impacting CO2 emissions.

CO2 emissions aren’t the only thing SUV sales impact

Pickup trucks also produce CO2 emissions, and, like ‘traditional’ SUVs, are also body-on-frame vehicles. However, in its 2019 World Energy Outlook Report, the IEA found that it was SUV and not truck sales that cut into overall ICE vehicle fuel savings.

So, not only are crossovers and SUVs cutting into CO2 emissions savings, but they’re also canceling out non-SUV efficiency improvements. And it’s partially because of SUVs’ increased popularity that the average US vehicle’s fuel economy rating decreased in 2019, Roadshow reports. Though admittedly, pickup trucks were also partially responsible.

The growth in SUV sales leads to another problem, or rather, several related problems. Specifically, safety-related problems. Numerous IIHS studies have shown that crossovers’ and especially SUVs’ designs have made road conditions less safe for pedestrians and other road users. That means drivers in non-SUVs, motorcyclists, and cyclists.

Plus, SUVs are now so prevalent that the IIHS is creating a more-severe crash test to reflect the increased average vehicle weight. Though, to be fair, pickup trucks also have a hand in this.

What can be done going forward?

Admittedly, EVs still have some work to do. Extracting the raw materials, especially cobalt, for their batteries still takes a human and environmental toll. Though The Drive points out, overall EVs still produce fewer CO2 and other emissions than ICE cars, SUVs or otherwise.

The solution, therefore, isn’t just building more EVs. Partially because they’re still not cheap enough, but also because convenient charger access is still an issue. And building electric SUVs, while already occurring, also has its downsides.

Firstly, as the IEA points out, larger vehicles are inherently less energy-efficient than smaller and lighter ones. Furthermore, to increase the range on an electric SUV or truck means a larger and heavier battery pack. That cuts down on the range, so you need a bigger pack, and…you get where this is going.

True, weaning the general populace off of large ICE vehicles via large EVs will likely be a necessary next step. However, what’s really needed is a cultural shift away from large, expensive status symbols to inexpensive, smaller cars. Big passenger cars won’t ever go away entirely, not if a family can only afford one vehicle. But instead of buying SUVs, maybe get a wagon or a minivan instead.

Follow more updates from MotorBiscuit on our Facebook page.