Classic Cars Aren’t as Powerful as You Remember

By any measure, having 700+ hp in a road-legal car is impressive in any era. But looking through how much horsepower some classic cars offered, on paper, some might think we haven’t progressed that far. Although it’s an extreme example, some estimates peg the supercharged Shelby Cobra 427 Super Snake’s output at 800 hp. However, the truth is that the way we report horsepower has actually changed over the years. And ‘hp’ itself is just one in a confusing array of units.

SAE ‘gross,’ not ‘net’ ratings have to do with classic cars’ high horsepower figures

While the Super Snake is an outlier, the Shelby Cobra 427 is a great way to demonstrate the discrepancy in classic cars’ horsepower ratings. And it has to do with the switch from SAE ‘gross’ horsepower to ‘net’ horsepower.

Back in 1965, Car and Driver reported the original, classic Cobra 427’s 7.0-liter V8 made 485 hp and 480 lb-ft. Considering the 1990 Dodge Viper RT/10’s 8.0-liter V10 ‘only’ made 400 hp, that figure seems impressive. And it becomes even more so when you look at the Cobra 427’s modern-day successor, the Superformance MKIII-R.

Although the Superformance MKIII-R can accommodate a 7.0-liter V8, it can also take on the Ford 7.3-liter ‘Godzilla’ V8. But while said engine can be easily modified to make more horsepower, in stock form it ‘only’ makes 430 hp and 475 lb-ft. Based on that, it seems like the MKIII-R is a bit outgunned.

However, that’s not actually the case. That’s because American automakers originally reported the SAE ‘gross’ horsepower of their engines, Car and Driver explains. Then in 1973, they switched to using SAE ‘net’ horsepower instead.

Why does this matter? Because when the switch happened, all of a sudden, engines seemingly got weaker. But that wasn’t necessarily the case.

What’s the difference between SAE ‘gross’ and ‘net’ horsepower?

To be fair, the introduction of the catalytic converter did ‘choke’ engine output somewhat initially. However, the switch from SAE ‘gross’ to ‘net’ horsepower had a significantly larger impact on posted ratings, Hagerty reports. And that’s even though that the engines themselves didn’t change. What did change, though, was how the engines were tested.

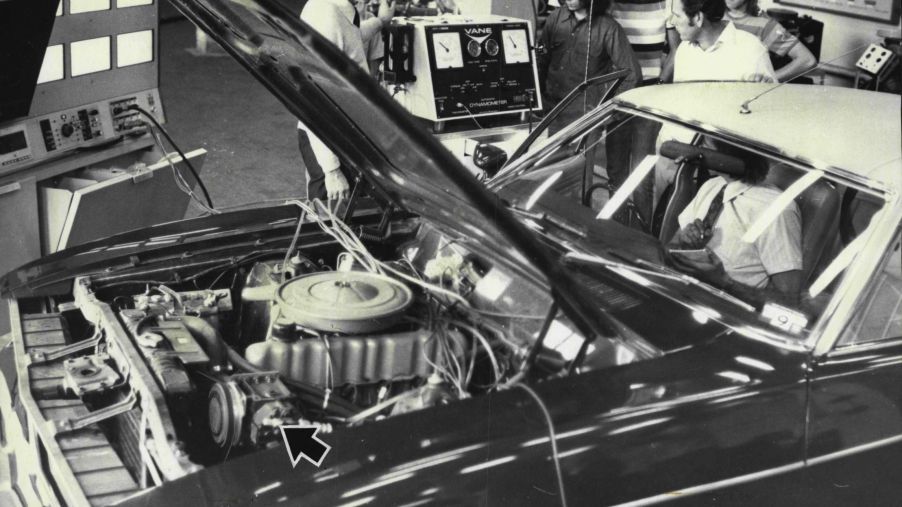

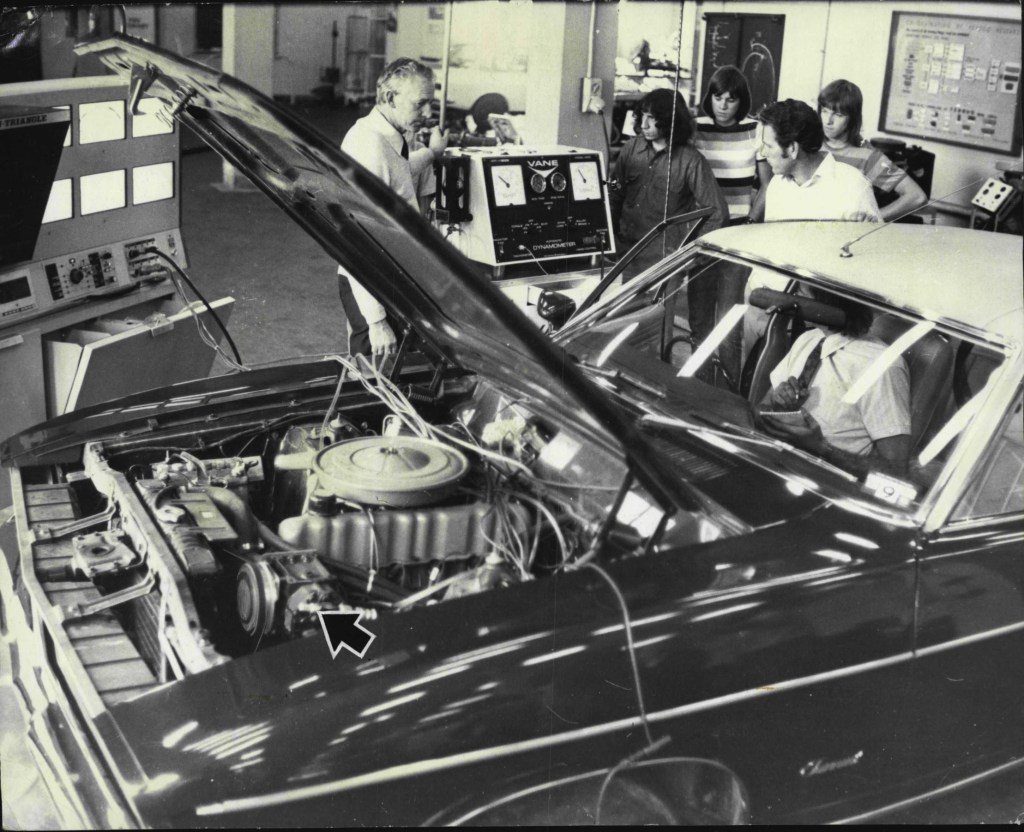

Then as now, horsepower and torque were measured on a dynamometer. But while you can measure output at the wheels with a chassis dyno, the manufacturers typically use an engine dyno. This measures output at the flywheel, Hardtail explains, which eliminates drivetrain loss.

Both SAE ‘gross’ and ‘net’ horsepower test standards involve an engine dyno. However, under the ‘gross’ standard, manufacturers could run the engine with “optimal” timing, no mufflers, and no engine-driven accessories like the water pump or alternator, AteUpWithMotor explains. That last part is crucial because the more accessories the engine drives, the more power it uses up. For example, when I run the A/C in my ’99 Miata, I can feel the compressor sapping horsepower.

Because ‘gross’ horsepower tests didn’t reflect real-world scenarios, the SAE switched to the ‘net’ system. Automakers could still run engine dyno tests, but with stock timing, stock exhausts, and every engine-driven accessory installed. Thus, 1972-model-year classic cars are noticeably weaker on paper than their 1971 versions.

There’s no set way to convert an SAE ‘gross’ horsepower rating to a ‘net’ one, but there are some empirical formulas, Hagerty reports. These rely on the car’s curb weight, ¼-mile time, and ¼-mile trap speed to extrapolate a ‘net’ rating. Using Car and Driver’s Cobra 427 figures, for example, it seems the 7.0-liter V8 ‘really’ made 340-345 hp. The snake’s bite doesn’t seem quite so scary now, huh?

We still have unit issues, but electric cars may solve them

Horsepower testing standards haven’t remained static since 1972, though. Back in 2004, the SAE updated its ‘net’ standard “to close some loopholes,” Car and Driver reports. As a result, published horsepower ratings briefly dipped again. The new standard also brought the SAE’s methodology closer to European standards, which brings up the other issues with horsepower ratings.

Firstly, the ‘horse’ in ‘horsepower’ essentially comes from a marketing ploy. And a horse makes more than 1 hp, Cars.com reports. Secondly, the numbers you see in publications are ‘peak’ ratings.

Finally, not every country has the same definition of what the ‘horsepower’ unit represents. As a result, an imperial horsepower (hp) is different from a metric horsepower (PS). And converting between the two causes rounding errors, Hagerty explains. There’s also something called ‘brake horsepower’ (bhp), but that’s measured the same way as ‘net’ horsepower.

However, there is an easy way around all of this. As more manufacturers embrace electric cars, they’re often quoting their EV motors’ output in kilowatts (kW). That’s a universal unit that’s already used in several countries for ICE cars. True, going from ‘hp’ to ‘kW’ would mean lower on-paper numbers. But if classic cars used kilowatts, we might not have this confusion today.

Follow more updates from MotorBiscuit on our Facebook page.