Two-Stroke Engines Got Strong Thanks to Rocket Science

Exhaust gas rocket science in two-stroke motorcycle engines article highlights:

- Modern two-stroke engines have high horsepower per liter figures due in part to rocket scientist Walter Kaaden

- Although Kaaden didn’t invent a specific feature, he developed the modern two-stroke exhaust header shape that effectively used gas flow to increase power

- The latest two-stroke dirt bikes still rely on the techniques Kaaden refined, though that hasn’t helped them become street-legal

Cars have more parts than motorcycles, but both have intense amounts of thought, sweat, and math poured into every detail. And seemingly minute—and oft-overlooked—changes to those details can often have surprisingly big results. Just look at how things like vortex generators and splitters impact racecar behavior. But making such changes sometimes requires outside help. And in the case of developing the modern two-stroke engine, it required a genuine rocket scientist.

A WWII rocket scientist helped boost two-stroke motorcycle engine power

Although they have their flaws, two-stroke engines also have several advantages over four-stroke ones. They’re simpler, lighter, a bit easier to maintain, and chiefly, have higher specific outputs. In other words, given engines of equal displacement and cylinder count, two-stroke bikes make more power.

However, that wasn’t always the case. Admittedly, no early internal-combustion engine was powerful, whether it had a four-stroke cycle or a two-stroke one. But around WWII, two-stroke motorcycles ran into a power wall, especially after regulations changed. Because of how they work, two-stroke bikes’ pistons heated up twice as fast as four-stroke ones, Cycle World says. Also, while increasing rpm helps four-strokes make more power, the same doesn’t apply to two-strokes because of their designs.

One of the motorcycle companies most affected by the changing two-stroke racing regulations was DKW. Before WWII, the German company used supercharging to get around two-stroke engines’ scavenging issues—more on this later. But with that banned, DKW, now named MZ, needed a workaround. And while several engineers created snippets of the ultimate answer, it was Walter Kaaden who pieced them together.

Kaaden was an honest-to-goodness rocket scientist who wanted to do something more peaceful with his knowledge after the war, Popular Mechanics explains. He found that something with MZ’s racing arm fittingly called ‘MZ Racing.’ Here, he took the ideas previous DKW engineers like Erich Wolf had developed and refined them with his knowledge of gas flow and resonance. And saying they made a big difference is an understatement.

Before Kaaden’s work, MZ’s two-stroke engines topped out at slightly over 100 hp/liter. But using just an oscilloscope and metal-shaping techniques, Kaaden got it up to 200 hp/liter, PM says. Keep in mind, the Bugatti Chiron hypercar makes 187.5 hp/liter.

Making rockets and two-stroke engines more powerful is exhausting work

It’s worth noting that Walter Kaaden didn’t invent anything, Cycle World says. Rather, he combined and refined several disparate ideas into one very successful one. And it involved the exhaust.

Rather than using valves, two-stroke engines cover and uncover their intake and exhaust ports using their pistons. But they still need those ports because, like four-stroke bikes, they work by sucking in fuel and air and blowing out waste gases. And those waste gases travel down exhaust headers and pipes, as they do in four-stroke motorcycles. However, even the best-designed exhaust and intake systems cause some waste gases to hang around in the combustion chamber. This dilutes the fresh fuel-and-air mixture, which means the engine makes less power.

Here’s where Kaaden’s knowledge of gas flow and resonance comes in. Gases flowing through pipes create pressure waves and resonate at specific frequencies—it’s how brass and woodwind instruments work. Wolf realized that he could use these pressure waves to his advantage, but couldn’t quite optimize his designs, Cycle World says. But Kaaden could.

Using his oscilloscope, he monitored the exhaust header’s resonance at different rpm. He then reshaped it and checked the frequencies and flow again. Repeat ad nauseam, and he ended up with the familiar bulbous two-stroke engine exhaust header we’re familiar with today.

This shape let the exhaust gases exit quickly, creating a low-pressure wave that sucked in more fuel and air. But it also created a back-pressure force that prevented too much fresh fuel and air from leaking into the exhaust. It’s not quite forced induction a la turbocharging or supercharging, but it’s not too far off, PM notes. And Kaaden’s work was so influential, modern two-stroke dirt bikes still rely on the principles he laid out.

They’re strong, but emissions (mostly) keep them off the road

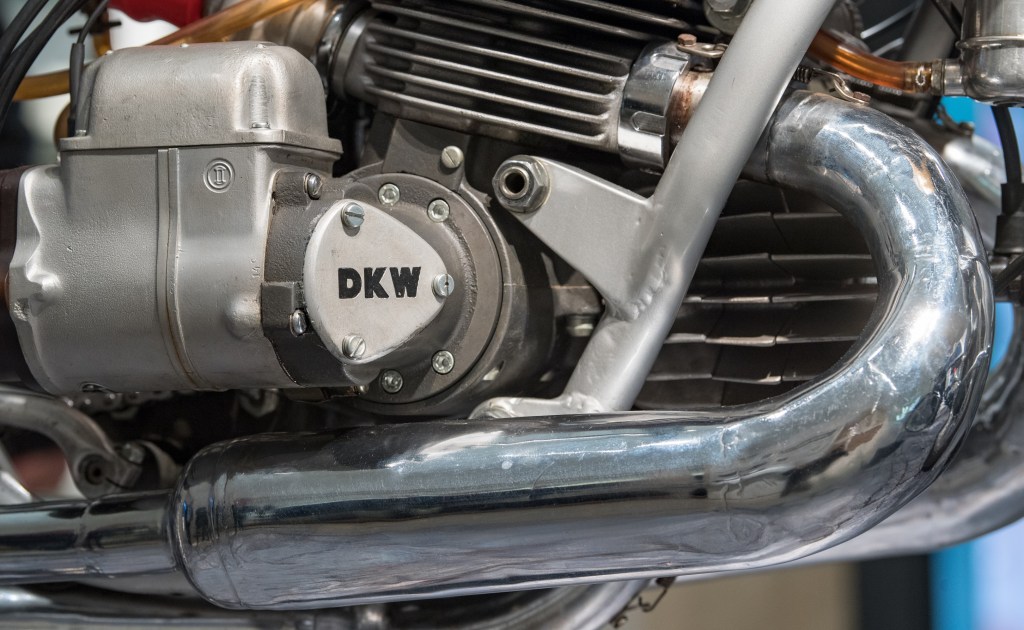

The exhaust header on a classic DKW 350 RM two-stroke motorcycle | Hendrik Schmidt/picture alliance via Getty Images

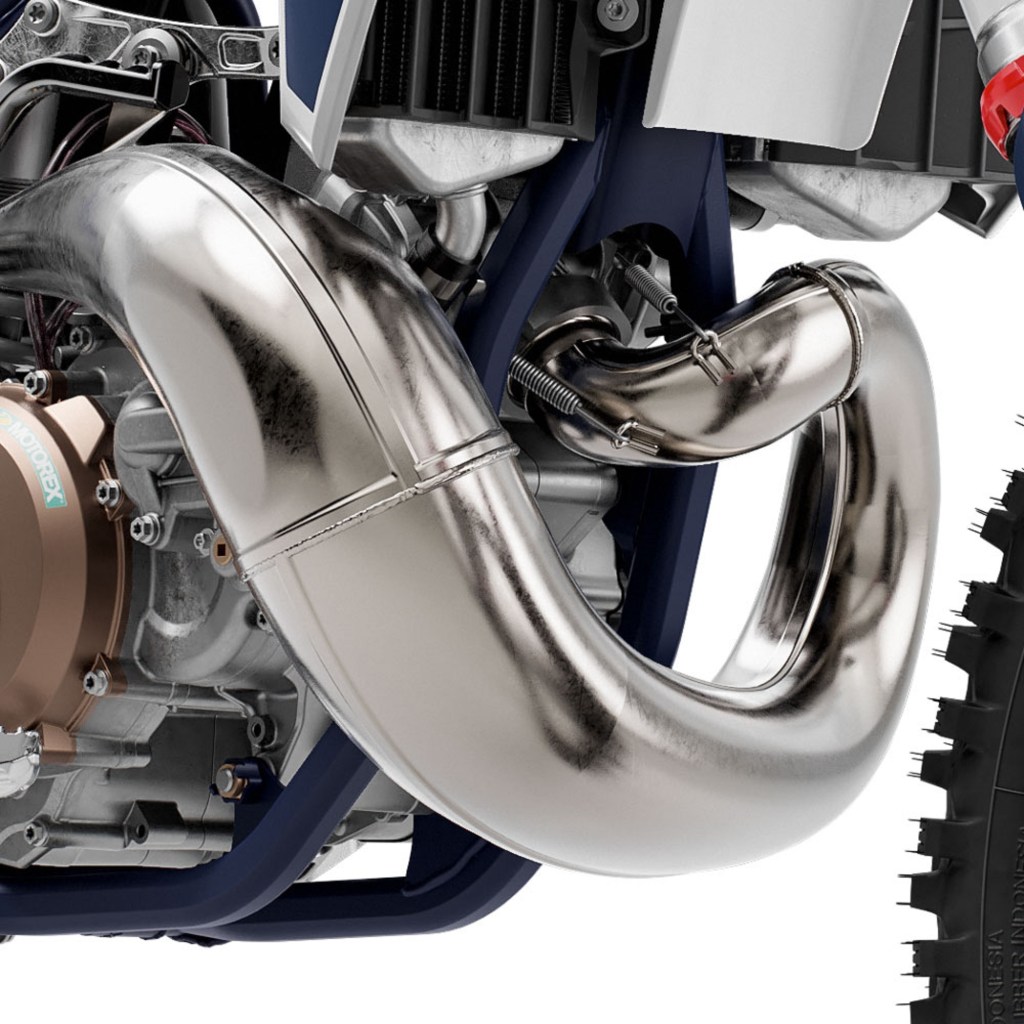

The exhaust header on a two-stroke 2022 Husqvarna TC 250 dirt bike | Husqvarna

However, while MZ Racing had some success with Kaaden’s two-stroke engine improvements, it wouldn’t last. After falling out with Kaaden, racer Ernest Degner took his former partner’s designs to Suzuki, PM reports. Suzuki used them to improve its race bikes, one of which Degner rode to win the 50cc World Championship. Kawasaki then clued into this new two-stroke tech, and after that, the oil-scented cat was out of the bag.

Unfortunately, while Kaaden helped make modern two-stroke engines powerful, he couldn’t clean them up that much. Remember those flaws I mentioned earlier? No matter how good their scavenging is, two-strokes always eject some unburned fuel out their exhaust. Also, they aren’t lubricated like four-strokes are—you have to mix two-stroke oil with the fuel. That means two-stroke engines burn oil, which causes even more pollution.

Admittedly, with modern direct-injection technology, two-strokes can be just as clean as four-stroke ones, Cycle World claims. However, it wasn’t available in the 1980s, when the EPA really started getting serious about emissions. So, to play it safe, most companies stopped trying to make street-legal two-strokes in the US.

And in today’s supplier-driven world, continuously refining two-stroke tech to reduce pollution would be considerably more expensive than buying an off-the-shelf solution. Plus, the rise of electric motorcycles and lawn equipment arguably makes the notion pointless.

Still, it’s cool to think that there’s a bit of rocket science in every two-stroke motorcycle engine.

Follow more updates from MotorBiscuit on our Facebook page.